|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Robert Lee ExtromArlington Heights, Illinois - "I remember that we were walking in some rice paddies and I was trying to stay on top so I didn't get my boots too wet. I was following behind Captain Corley when he turned around and said, “Extrom! Back off! You're drawing too much fire!” That's when I realized that the bubbles in the water were from sniper fire." - Robert Extrom The completion and posting of this memoir |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

Pre-MilitaryMy name is Robert Lee Extrom of Arlington Heights, Illinois. I was born April 6, 1930 in Congress Park, Illinois (now part of Brookfield, Illinois), a son of Harry Arthur and Frances “Fannie” Goodyear Fincham Extrom. My father was born in 1887 in Holdridge, Nebraska, and my mother was born on May 27, 1891 in Streator, Illinois. Dad's family was from Sweden and Mom's family was from England. It should be noted that the family name was Magnus/Magnuson and apparently changed just before they migrated to America. The reason for the name change is unclear. One story said that Sweden had compulsory military service requirements and the family of Magnus had five sons and one daughter. With their plans to go to America soon, they apparently figured a name change would forestall the military process and not hinder their plans. If this was so, it worked. They came over in the mid to late 1870s. My great grandfather

Magnus was a farmer. Somehow they ended up in Central Illinois.

Around 1883 some of the family, including my grandparents Petter and

Christina Extrom and their one daughter at the time (Ellen, born

June 1882 in Illinois), decided to go west to Nebraska--perhaps for

homesteading, in 1883. They worked as transient farmers for

about ten years in the Holdridge, Nebraska area. Their second

through sixth children were born in Nebraska. We were told that they

lived for some time in a “soddy” house and as farm hands in and

around Holdridge. If Nebraska had had enough timber, I’m sure they

would have built a log structure in quick time. My dad had a twin

sister named Maude. My Uncle Bill was born in Nebraska in May 1889. He

later in life became a policeman in LaGrange Illinois. The Petter

Extroms then came back to Illinois in the early 1890s, got their own

farm, and had three more children to round out the nine I came into a crowded family. My parents had ten kids but my mother raised twelve as my oldest brother had two small sons whose mother died. The three of them came to live with us. My siblings were Donald Harry Extrom (born in Winona, Illinois, in 1911), Marjorie Eulola Bergstrom (born in 1913 in Ancona, Illinois), Kenneth Albert Extrom (born in 1914 in Ancona), Dorothy Mae Bergstrom (born in 1917 in Winona), Betty Jane Extrom Seaholm (born in 1921 in Cicero, Illinois), Arthur Roland Extrom (born in 1922 in Brookfield, Illinois), Dale Franklin Extrom (born in 1924 in Brookfield), Ellen Ruth Sutton (born in 1925 in Streator, and Edith Laurene Reinmuth (Fisher) (born in 1927 in Streator). Marjorie and Dorothy have the same last name because Marjorie married Carl Bergstrom and Dorothy married George Bergstrom. Carl and George were brothers. All ten children were born at home. Hard to imagine, even with a midwife helping. Just think of all the cloth diapers they went through and that had to be washed, strung on a line to dry, folded, and put away. Mother always had calloused fingers (sometimes bleeding) from getting stabbed by the diaper safety pins over and over again. My parents farmed in the Winona, Illinois area. Farm families wanted big families because that's where they got their labor. One of the moms who lived in the flats helped my mom with the babies. I was close to my parents and siblings, although my sisters had arguments about who took care of me the most. As the youngest, I often felt like I had more than one mother. Before my folks were married, my paternal great aunts (Ellen, Mabel and Birdie) used to go hunting for fun. It was like men going fishing. If the women got some squirrels or rabbits, they brought them home. My grandma hunted in her earlier years. My mother did not hunt. Most likely my aunts learned to hunt from my grandfather, Jan Petter, on his farm. My folks moved often, always renting until 1941 just prior to Pearl Harbor when they bought their first home for about $5,000 in Downers Grove, Illinois. The family came off the farm just after the first World War, about 1919 or 1920. Our folks had four children at that time (Donald, Marjorie, Kenneth, and Dorothy.) The first move to the Chicago Suburbs was to Cicero where in July 1921, Betty was born and became their fifth child. Dad wanted very much to work in the up-and-coming automotive business which had started to boom, but jobs were scarce and he took what he could get. Initially that amounted to various and numerous jobs. Selling vacuum cleaners and other door-to-door products and doing some part-time repair work at an auto dealership. He and his brother Bill took up a little moving business using Bill’s small truck for local moves. My family moved to Berwyn, Illinois--a few miles away from Congress Park, in 1928. I was born there on April 6, 1930. Ruth (or Edith) was born in the 1920s. My parents primarily moved because my father didn't like farming. After leaving the farming business, my dad worked on farming equipment, keeping the machines running. During harvest, he went with the big equipment (mostly steam engines) to keep the machines running. He also worked on machines used to pull equipment. Dad really could fix anything with a motor. He seemed to be able to remember precisely the sequence of tearing apart mechanical items and reassembling them was no problem. Dad Takes a FallOn one very stormy evening, upon walking home from a bus or the “L” line Dad sought shelter in a building under construction. He stepped through a door opening only to suddenly fall some eight or nine feet into an excavation hole, breaking a leg in three places. He passed out in the wet muddy hole until dawn when he came to and began to yell for help. A milk delivery wagon came within his shouting range. Somehow help arrived and he was taken to County Hospital for surgery and rehab for ten or twelve days. My Uncle Bill picked Dad up and took him home from the hospital where he would be bedridden for four to six months. Dad was 26 or 27 years old, and my parents had no income when he was injured. When that happened, three or four of the kids went to live with cousins in Streator. Dorothy, Betty, and Ruth went down for six or eight months to live with relatives who didn't have as many mouths to feed. A close neighbor of the folks was a great help for Mom with baby duties and supplying food and general support during this rough period. Finally the family was brought back together just in time for another member to come along as our family moved to Brookfield. The exact timing of events is sketchy. Art and Dale were born in Brookfield. Ruth and Edith were born in Streator in 1925 and 1927, respectfully. Apparently Mother’s sister (Edith Cramer) in Streator was able to help her out. Aunt Edith used to say, “She’d have one baby, then our mother (Fannie) would have two before she has a second one—and on it went." Extrom Bike and Lawnmower Repair ShopIn the latter part of 1930, our family moved from Congress Park to South Madison Street in Hinsdale. We have a group picture of the family at that time with me on mother’s lap—at that crawling age. The house is still there. After two or three years on Madison Street they moved a short distance to South Grant Street and 55th Street on a corner lot. That house still stands. Too bad they couldn’t have kept it for the Sound Hinsdale High School was built a block and half away. I started school at Madison Elementary, just three blocks from home. I walked to the school from Kindergarten to third grades. Around 1933 or 1934, Dad took out a loan and bought a little tire shop and started the Extrom Bike and Lawnmower Repair Shop located in Hinsdale near the railroad tracks (near York and Ogden Avenue.) Dad was out and gone from the house by 7 a.m. and didn't get home until 7 or 8 at night. Later in life he developed arthritis, but he was able to be at the shop until his arthritis became debilitating. In 1941, the family business picked up. They had built up more bicycle work with gas rationing on (because of the war). They also picked up lawnmower sharpening work, even repaired washing machines, vacuum cleaners, skate sharpening, almost any type of household and yard garden equipment. For awhile we even got into sporting goods. We became a “Schwinn Bike Dealer” and would you believe it, I never, ever had a brand-new bike. I always had a rebuilt one that I ended up painting and assembling. But it got me where I needed to go for the 4th of July. Seven to eight of us always rode decorated bikes in the Hinsdale parade advertising “Extrom Cycle and Service.” We had one car when my dad started his business. Dad bought an old car and worked on it. He just loved mechanics. He always had a car—the oldest one that still ran. Then eventually when we were on York Road, he bought a paneled, closed-in truck, and that's what he used for picking up bicycles or other things he could use. Eventually my brother Don bought his own car. I don't remember Mother driving or getting her license. She could drive a horse and buggy. (Before I came along they had a horse and buggy.) The family moved again to the north side of Hinsdale on York Road, a block from Ogden Avenue. We had a large lot and a barn, orchard, and a lot of trees to climb in. The house was quite run down with a gloomy gray paint, peeling exterior. In Hinsdale, we attended Sunday School at a Baptist church. Sadly, I can’t recall my folks going to church, but I do recall Dad reading his Swedish Bible on Sundays. We then lived in a three-bedroom apartment in Hinsdale, Illinois on Grant and York Road on the south side. There was one bedroom for my parents and two bedrooms for my siblings and me—three or four kids to a room. When I was about two years old we moved to the north side near the dam. At that time Hinsdale was a town building up. There was a lot of space, but I would not call it rural. We moved from Grant Street because my parents were renting houses then. Much of the bike shop work was seasonal, so Dad had to take out some small loans to pay the rent or fix the car. In our York Road residence we were less than a mile from Fullersburg Forest Preserve, Salt Creek, and the Old Grau Mill. That was our “playground.” I learned to swim in that dirty creek, as well as ice skate, play hockey, and do some fishing. At the boat house, we helped clean row boats and canoes that were rented out and by doing so, got to use them when they weren’t busy. I remember once we skated from Hinsdale to Western Springs-LaGrange area, which had to be a ten-mile round trip. It took us at least three hours. John Petter and Christina Moblad ExtromAs far as I know, Grandpa Pete never visited our home. We saw him in Wenona, Illinois, and usually at the Extrom Reunions. My first memory was being somewhat scared upon seeing him—his ruddy wrinkled face partly obscured by a massive mustache covering his upper lip. I recall he spoke with a Swedish accent. We (kids) were not schooled in the Swedish language, so when some of the elder relatives conversed in Swedish we figured it was something we were not to know. My dad seldom spoke in Swedish. Grandpa Pete was born in Vase (Varmland, Sweden) on November 20, 1855 and died in Wenona on March 12, 1946 at age 90. Grandma Christina Moblad Extrom was born February 2, 1854 in Sweden and died on November 9, 1925 in Wenona at the age of 71, before I came on the scene. Hence, I didn’t know her. Petter and Christina were married in Varna, Illinois, on November 4, 1881. Christina’s mother was Kayse Forslaf of Sunne, Varmland. Christiana had a twin sister Marie, of whom little is known. She also had a half-brother, E.G. Moblad, who lived in Chicago. [NOTE FROM FAMILY: We have since learned more about Christina. She has quite a number of half-siblings. It’s a sad story from another time and to retell at another time. Let it be known, it was quite trendy after immigrating to tell bogus stories portraying immigrant’s illegitimate royal heritage, whether in jest or to hide truth. Bob was told that Christina’s father was supposedly a member of the Swedish Royal family, but in actuality that was a fabrication.] Grandpa Pete had five siblings: Charles (settled in Oklahoma), August (settled in Illinois), John (settled in Illinois), Louise (settled in California), and Andrew (settled in Illinois). Our grandparents had nine children, thirty-two grandchildren, thirty-six great grandchildren. At death, Petter was survived by one brother—August Extrom of Varna, Illinois. Our own parents helped swell the rank in all offspring categories. Harry Extrom and Siblings:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ellen Theresa | b. June 29, 1882 | Born in Varna, IL | d. February 2, 1964 |

| Selma Emilia | b. February 21, 1884 | Born in Holdridge, NE | d. June 11, 1960, Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Charles Elmer | b. September 26, 1885 | Born in Holdridge, NE | d. May 30, 1946 |

| Harry Arthur | b. July 14, 1887 | Born in Holdridge, NE | d. May 14, 1963 |

| Maude Agnes | b. July 14, 1887 | Born in Holdridge, NE | d. June 12, 1974, Lakefield, MN |

| William Rudolph | b. May 30, 1889 | Born in Holdridge, NE | d. May 19, 1968, LaGrange, IL |

| Mable Olive | b. August 20, 1892 | Born in Wenona, IL | d. October 23, 1977, Streator, IL |

| Berdie Marie | b. May 22, 1894 | Born in Wenona, IL | d. March 31, 1975, Memphis, TN |

| Lloyd Leonard | b. March 14, 1896 | Born in Wenona, IL | d. June 1973, San Bernardino, CA |

Growing Up Poor

We grew up poor, but we didn't realize it. Everyone was in the same boat. Although there were some wealthy people who lived in Hinsdale, ran businesses in Chicago, and commuted by taking the Burlington, they weren't affected by the Depression like the rest of us. During the Great Depression people lost jobs and stores closed, but the bike shop survived because we started to fix other items like sewing machines and radios. I worked at my dad's shop, but I didn't get paid. I worked on bikes, painted them, and fixed them. Of course, I worked under the supervision of my brother Don (and later my brother Dale), who took over the business when Dad began suffering with rheumatoid arthritis. The family business moved to Case and Ogden Avenues in Westmont Illinois in 1944. Don moved the shop to Lisle, Illinois (still on Ogden Avenue) in 1963 and Dale took over when Don died.

I drove the truck for pickup and delivery, mostly lawnmowers, and I swept the floor. In those communities especially, many times the kids had to go to work. Kids dropping out of school was almost more normal than abnormal. My siblings Dale and Edith graduated, but Marge, Dorothy, Ken, Don, and Ruth dropped out of school when they were 15 or 16. Art didn't get his high school diploma until he left the service. Even when they were going to school, when they did get a job they had to bring money home. Almost all the kids had to work. They were expected to work if not busy elsewhere. Betty used to housesit for a doctor who had kids. She spent her summer times and a couple of days a week there.

In those days, if we got twenty-five cents an hour, we were rich. Probably the only thing that helped us survive was when Don got a job at the A&P butcher. We always got meat at a discount or before they threw it out. In those days, they didn't have the big freezers to keep stuff in like they do nowadays. When my brother Kenny went to work for Piggly Wiggly, he brought home leftover stuff that didn't sell. We went to shops for day-old bread and stuff like that. This was just normal for everybody. We always had a large veggie garden and Mother (with help) did a lot of canning of fruits and vegetables.

The way we lived was like The Grapes of Wrath. We came looking for a job and we took what we could get. We couldn't be choosey. Being industrious was built into us. It didn't matter what our age was. When we lived in Hinsdale, to earn a few extra coins we picked the lilacs on Memorial Day. (I shouldn't say this, but we swiped a few tulips that didn't grow in our yard, but in our neighbor's yard.) Then we went to York and Ogden and sold them for twenty-five cents a bouquet. People bought them because in those days there wasn't any other option. There weren't floral shops like we have now. If somebody could get something for a quarter, they bought it instead of spending a buck and a half. That's how we earned our spending money. If we had a little money we could get a foot-long hot dog or a pop or go to a matinee because they were cheaper on Saturdays. We could see the newsreel—we were educated there.

We hunted, fished, and grew veggies. My brother Don moved back home with his two boys when his wife, Clara, died after going into a diabetic coma. Clara was just twenty-six years old. The kitchen table wasn't large enough for all of us to eat at one time, so we ate in shifts that depended on who had to leave first. Supper was the same. Lunch was a peanut butter sandwich and an apple off the tree. We had an orchard back in Hinsdale. Two of the houses had orchards with fruit trees. We also had a grape arbor. We had a mini-farm, so we raised our own chickens for a while. I used to help Don when he killed two or three chickens on a Saturday for Mom to prepare for Sunday dinner. (It took about three chickens per meal.) My brothers whacked their heads off and I remember watching the headless chickens running around spurting blood all over the place until they became motionless. Then they were soaked, plucked, gutted, and cleaned, ready for cooking. We ate a lot of chickens in those days.

We bought a lot of our clothes at second-hand stores and rummage sales. More than half our clothes came from those places. (I didn't like it when I got my first knickers. They rubbed together.) My dad used to cut all the boys' hair and that was before they had electric shavers. Laundry was the biggest household chore. Every Monday, regardless of the weather, Mom had us strip the beds. We probably had four bedrooms on York Road and if there wasn't a bedroom for someone, then there was a bed in the hallway where the landing was. In those days we didn't have as many clothes to launder because we wore our clothes over and over. The biggest things were the underwear and socks. Of course, Mom wouldn't let the boys handle the girls' underwear, but we had to help by putting the clothes out on lines. In the winter we hung them in the attic. It took forever to dry them. I had to match socks. If we got a hole in one of them, we darned it—we didn't just throw out socks because they had a hole.

One thing I can say about a town like Hinsdale, in those days it was probably one of the wealthier areas. The people who had resources were pretty generous in our terms. So if we cut their grass for money, they paid well. There wasn't welfare in those days, so if they knew there was a family in need they sometimes helped them. Art quit school to work for Butler—the polo ranch. He loved horses. I don't remember how they paid, but it wasn't too bad. Some of my early friends became millionaires—the Cushings and the Ketterings. They got their money through their family and education—the Sloan/Kettering Research. Many of them made money through real estate ventures and a lot of people who had pretty good jobs in Chicago in those days (like store managers) had a better income.

There weren't too many that went out west to the cowboy belt or gold mines, but I had an uncle who went to California. It was not like a wagon trip. It's surprising how those old cars got there. I don't know how they did it. There were not gas stations like there are now. Travelers had to bring extra gas with them and tie it on the side. My dad's brother Charles went to Oklahoma.

Desire for a Better Life

Chicago went through a transition in those days. There were those who went through some despair, and when they got a few bucks went to the local tavern. But my mother never had any alcohol in the house. She got angry if my brother or Dad took any of us kids into a tavern. We weren't supposed to go into any bowling alleys either. There were certain places we were not allowed to go into because Mother said it would corrupt us. She was a Puritan, meaning she had high moral standards. My dad had high moral standards, too, but my mother spoke it more.

My mom and dad had the desire for a better future. When we moved to Downer's Grove, I usually went to my dad's shop on Saturday. (It was open for business six days a week.) During the week it was too expensive to pay the train fare from Downer's Grove to Hinsdale, so my dad drove the truck. Sometimes I went with him and sometimes I rode my bike the five or six miles from Downers Grove to Hinsdale if I had something to do later in the day.

I remember coming home one time when things weren't going too well at the shop. Like any small business owner, my dad performed work for people–-fixing washing machines, vacuum cleaners, fans, and electrical stuff, as well as bikes and lawn mowers. That day he was really dejected. Probably this was during the war, because a lot of war industries had started up. It seemed like the people who had regular jobs were also getting tight on paying their bills. That was one of the biggest things we had to confront. My sister Edith had to call people who were more than thirty days behind in paying their bills. We didn't think of charging a fee in those days if someone was late, but we probably should have. Collecting money for work performed became a big thing. People used to pay their bills real good, but it seemed like the wealthier they got, they just thought it was a little bill. But it wasn't a little bill to us.

We were coming home from the shop on a Saturday. I can't recall what my dad was talking about, but I remember that he started crying as he was driving. At that time my dad was probably pushing sixty and he, I think, just felt that he didn't have much to show for it. He felt very sad that he couldn't give us what other kids had. It was the first time I ever saw any emotion in my dad. He was pretty stern, but he had a heart about things. It was a side of him I hadn't seen before. Our family started in World War 1 in 1914. There were ten kids born over nineteen years. I think my folks were in a depression their whole married life, although their business started to do better right after the end of the Second World War.

Quarantines and Vicks

In those days doctors made house calls. I had measles for two weeks and a fever. The doctor came to us because we weren't supposed to go to him if someone had a communicable disease. Certain measles were quarantined by the doctor. My nephew Dick was quarantined with whooping cough. I don't think he was two years old yet. I remember having signs on the door that said, “Don't come in here. You can come to the door, but you can't come in.”

My mother used hand-me-down folk remedies. She gave us castor oil and aspirin when we were sick and used Vicks. If we had an earache she used to heat oil of some kind and put it in our ear warm. There weren't prescriptions in those days. Even the doctors gave us stuff they carried around.

Christmas & Other Get-togethers

In those days my parents' activities revolved around their churches, but with twelve children to rear and a business to run, I don't remember just how involved they were with churches. Mother went to a congregational church in Streator. Dad went to a Lutheran church.

Christmas was hectic. We always had big gatherings. We had Christmas with our folks early in the morning about seven. That is when we had our Christmas presents that our folks made for us or bought at the Five and Dime. Then Ken and Eleanor, Don and Clara—whoever was married, had their Christmas with us later. We had a big dinner and spent Christmas Day together. It was the Cowboy/Indian era when boys got cap pistols, holsters, and play guns as gifts. I remember that my brother Ken got me a toy cow that mooed when it was moved. He wrapped it up and I didn't want anything to do with that present! One thing I wanted and kept asking for (and probably got when I was in fourth grade) was a pair of boots that had a pocket on the side where I could put a knife. Those were kind of cool.

In Hinsdale, when we moved to York Road, we were near Fullerburg Forest Preserve and McGraw Mill. That was kind of a hang-out place. We went ice skating there and played hockey. There was a boat house there that had canoes and rowboats. On a few occasions we were able to rent one. We used to go fishing down there. I learned to swim in the tributary of the Salt Creek. There were houses on the east side of the street and just farm land. We used to go swimming in the swimming hole. I'm surprised we survived that since cow manure washed in there.

Family Reunions

I remember our family reunions. They were a big thing for us. It was our family vacation for the year. The Extrom one was in Winona and the Fincham one was in Streator. Almost all those people down there were farm people. On the Fincham side, they were more business-oriented. My mother's brothers worked for Streator Brick Company, which was a big company. That was when they were still using brick for roads. My uncles did pretty well because the work was steady. During the Depression, the unemployment rate was like 25%. In 1926 construction was down two billion dollars in today's dollars. About 13 million Americans lost their jobs by 1932. The farmers were hit with the Depression. Many of them lost their farms, even though they had food.

The Petter Extrom reunions held in Wenona were special, well-organized in the early years, and well attended. Some 80-100 usually attended. In those days, most relatives lived on farms in Marshall County, Illinois, and any who had moved out of state or to Canada made efforts to attend the reunions every other year. If possible, they were held on the second Saturday in July. Postcards were sent out as a reminder to those living over 100 miles or so from Wenona.

At the reunion in Wenona Park, the younger active generation went

exploring, played softball and other games, toured the four-block

long town, climbed the old coal mind Slag Hill east of town (against

our parents' wishes.) Families arrived around 11 a.m., and after

greetings began to set out all the food in the pavilion, covered

carefully to keep the flies off everything. A call to eat rang out

at about 12-12:30. A prayer of thanksgiving was always offered.

Following lunch and cleanup of tables, a planned family program

commenced. There was

singing, of course, with cousin Alice Olson Evans playing

accompanist for duets, sextets, etc. Alice played the accordion or

portable organ. Pastor Joseph Hultgren (August Extrom) of Varna gave

a devotional and prayer. There was an update of Extrom

happenings—births, deaths, illnesses. Sometimes there were readings

or citations of poems/story, etc. They held an election of a

committee for the next year's reunion. The more local yokels always

were elected. The program ran a little over an hour, closed by

singing Blest be the Tie that Binds followed by a

benediction.

Sadly, the reunion event began to change after World War II. The older ones were leaving the farms, movement to urban and city life and the grim reaper took a toll. Families began to fragment. A remembrance I can’t forget is how our family was stuffed two-deep in our car. Dale, Ruth, Edith, and I were generally the lap-sitters on a two-hour or more drive with only a hot breeze to cool us. Perspiration always won out on the trip. Forbid that we got a flat tire, for we had to empty out all and everything at the side of the road, remove and patch the tire tube and hope it held until we got to Wenona. My first attended reunion was 1934 when I was age four.

McFadden Family Farm

A highlight stopover for some of us who were fortunate to be dropped off at Ray and Mabel McFadden’s family farm between Streator and Wenona after the reunion for a few days' stay--usually one or two at a time, depending on available space. It made the ride home less congested for the others. We tasted the real rural life—smells and all. The McFadden boys (Howard, Robert, George, and Dean) did their best to teach—tease and find a few easy chores they felt we “city kids” could handle. We got to ride an old tractor, ride their somewhat stubborn pony (Lady), and play hide-and-seek in the barn hayloft in 90 degree temperatures.

Most of all, I remember enjoying Aunt Mabel’s cooking and baking. Breakfast was the big meal of the day. I think she started baking and cooking before 5 a.m. Many chores were accomplished between 5 a.m.-7 a.m. Then we ate a breakfast that included meat, bacon, eggs, veggies, potatoes, fresh-baked rolls, chocolate milk, and coffee, of course. It couldn’t have been better. A year earlier, we had taken our German Shepherd dog, named Silver, down to the farm. We always liked to see how she was doing after being a “city” dog for three or four years. She was heavier (overfed,) but seemed to enjoy her open air freedom. Brother Don usually came back down to take us home. On one occasion sister Betty stayed at the farm and her cousin Robert McFadden enjoyed teasing her. The story goes that one morning at breakfast time Robert told Betty that some fresh fruit would be nice to have. He asked her to go behind the barn and pick some fresh bananas. Betty (naively at age 15) went out and found stalks of bananas and brought some in, stating that she thought bananas grew on trees. Bob responded, “No, we’ve been growing them just like corn for years.” You see, Robert had gone out and substituted real bananas in the corn husks to set Betty up. I’m sure they had a good laugh at dear Betty’s expense.

School Days

My mother graduated from Streator High. Dad got through sixth grade before quitting to work full-time on their farm. That was quite usual for that time period. Of their ten children, four went through the twelfth grade (Dot, Dale, Edith, and I). All the rest dropped out of school by the age of fifteen or sixteen to go to work. None went on to get a college degree.

I was well-behaved mostly. When I was at Madison School, we were putting on a play and when it ended I stuck my head through the curtains and stuck out my tongue. I attended kindergarten and first and second grade at Madison Elementary K-3, a public school. I was four when we moved over to 55th Street and Grant. I either walked or rode my bike to school. The summer before I started third grade we moved to the north side of town and I went to Monroe School. The school was about a mile and a half from York Road. I rode a bus to school once in awhile, but I usually rode a bike. I always took a bag lunch and bought a pint of milk for three cents.

In September 1941 we moved again--this time to 5337 South Lane Place in Downers Grove. We lived in a nice large house on a small lot. There were four bedrooms upstairs and there was a full basement (coal heat), but only one bath (upstairs), where there was always a line in the mornings. It had a one-car garage which later was used to store used bikes and old mowers for parts. Our truck and auto were parked in the back yard, which often created starting problems in the cold winters. My parents were just coming out of the Depression that year, and they bought a house that cost about $4,000-$5,000, I think. They bought it on a payment plan, paying about $50 a month. It was the first time my parents owned a house. Prior to that we moved around a lot, probably because my parents found a place that had cheaper rent. The house is still there. It was a rehab in recent years. It had new siding and windows, a driveway, and a sizeable addition on the back. That $5,000 price in today’s market is near $500,000.

I worked at the Butler Ranch. It had two locations—one in Hinsdale, Illinois and the other in Texas. I worked there in the summer along with other kids, including my brother Art. The youngest son of the owner, Paul Butler Junior, was spoiled. He went to a private school most of the time. He was always immaculate and well-dressed. (Eventually he got in with the Hollywood group later in life.) The older guys who worked at the ranch realized they had never initiated Paul, and felt he shouldn't have been treated any differently than anybody else. Those of us who were part-time at the ranch decided we should initiate him. We dragged him down to Salt Creek and threw him in the muddy creek. He had a beautiful riding outfit on. He got all muddy and gooped up. He was mad. We had to throw him back in the creek to wash him off. He went home and told his older brother what happened. His older brother wanted to get after the boys who initiated Paul, so he came out and asked, “Who did this to my brother?” We had to skedaddle out of there because he found his shotgun to scare us to death, shooting over our head. He chased us a little bit and then we went home and never went back.

I liked school and I liked all my teachers. (You had to.) I didn't participate in any extracurricular activities other than playing football in high school. I was a defensive linebacker, but I was one of the smaller ones, but I was a rather good tackler and back-up center. I was also a guard in basketball and played wherever they needed someone. I was encouraged to go out for sports even with only a five foot three inch frame plus 106 pounds. As a freshman I tried out for football. In those days they had lightweight and heavyweight divisions. Lights was anyone weighing under 140 pounds in August before the first practice started. Since they were usually short of bodies, few if any, were cut the first year. I was a light weight until my senior year. I usually played as a lineman and usually on the second team, but I did letter my junior and senior years. In my junior year, we were undefeated but shared the West Suburban Conference Championship with LaGrange, which also was undefeated. We had one tie each with LaGrange. In our senior year sports changed to the Fresh-Soph and Varsity level format. Dale had been first team at Hinsdale his sophomore and junior years, but was not eligible to play at Downers his senior year because of our move in September. Hinsdale and LaGrange were usually the powerhouse teams in football and basketball in those days.

Sister Edith was a good singer and had leads in Gilbert and

Sullivan operas put on for six or seven years at Downers. My brief

singing career was in my sophomore year in the chorus ranks as an

English “bobby”

(policeman) in The Pirates of Penzance. It was fun, but

sports were my outlet and desire so I

hung up singing.

When I graduated from Downer's Grove High in 1948, I had reached five foot ten inches, but just weighed 140 pounds. I made the honor roll in three semesters out of eight, but got lost somewhere in the class standings. Our class of ’48 was a rather uniquely-bonded group. Following our 50th reunion, a class newsletter was started and published twice a year. Florence (Hubbard) Babos (later of Fox River Grove) was the editor/publisher and very skillfully directed the “48 UPDATE” for nine years and some eighteen publications. Members of the class tracked and located nearly 98% of our class members. Besides keeping members up to date on happenings, special events, highlights from occupations and careers, travels, birthdays, anniversaries, family illnesses/deaths etc., Florence requested and compiled classmates' biographies for the newsletters, which helped bond us even more. Reunions were held every five years locally, while some regional ones were held in Florida, Arizona, Colorado, and Massachusetts. These were well-attended. The newsletter started out with being thirty pages long and grew to sixty-six and even seventy pages. I guess we got longer winded as we aged. In September of 2008 we had our 60th reunion in Lisle.

Effects of the Depression

No TV’s. No electronic devices. No cells. No stereos. How did we live? We did live better than cave dwellers. We survived childhood diseases and injuries—many home remedies worked quite well. There was no medical insurance in those days. Doctor’s office and examination fees were paid in cash and or even on an installment basis if needed. Their fees were low as were food prices. All was relative, I guess. All of us earned our own spending money. Newspaper routes, selling eggs, selling bouquets of fresh flowers at York and Ogden, grass cutting, leaf raking. Our clothes were mostly hand-me-downs, retailored, patched and clothing was usually purchased at rummage sales. Everyone was in the same boat financially so no keeping up with the latest styles or the Jones’s. It was sometimes hard, but we pulled together and most of our necessities were met.

Entertainment? There was just AM radio, a Victrola for 78 rpm records, piano playing (Mom), violin (Dad), singing (sisters mainly), newspapers, a few magazines, can’t forget comic books and marbles too. Play was imaginative: Kick the Can, Rover, Tag, Dodge Ball (don’t remember anyone getting hurt badly.) Now we’re made to be scared of playing anything that has the potential of injuries in the slightest and from lawsuits. With our family size, we played lots of softball. We had archery, Badminton, tennis, always horseshoes around even smaller rubber horseshoes us kids could use. Croquet, target shooting with BB guns, played Cowboys and Indians, Cops and Robbers, Robin Hood, etc. Many of us kids liked to explore the woods for arrowheads, etc, and search through abandoned houses and barns. Treasures were everywhere if one took time to look and dream and search from some. We did have good fun even when I got stuck high in a tree in our yard at age ten. I was playing “Look Out for the Enemy” and ended up getting my foot wedged very tightly in a fork in a tall tree while descending. It must have taken me a half hour to free my foot and finally work down to the ground. We were rather daring. Does this sound like Little House on the Prairie? Our family could have been somewhat like that story.

Mother was always the first line of discipline and control when any of us got out of hand or sassy. If we resisted her corrective action, the dreaded warning “I’ll have to tell your father when he gets home.” We seldom challenged her. We all learned the hard way—that one time with dad was usually enough to brand our memory to obey. With ten children, order had to be maintained. Mother was 39 years old when she had me and she had been through a lot by then. There was 18.6 years between their first son (Don) and the last son (me.) She raised two more 14 after me—grandsons Donny and Dick. Her life was always caring for others. Prior to getting married, [Note from daughter Janice: "Fannie also took care of her own mother after Eulola suffered a stroke."] She endured tremendous daily pressures, worries, stressful events to the point of a nervous breakdown. Several times I found her softly weeping sitting on the living room sofa when I got home from school in Downers Grove. I would hug her, not knowing what to say to her. [Note from daughter Janice: "Only a “manchild” would think a woman weeping was having a nervous breakdown. She was just releasing her stress, Bob! You kids probably did drive her bonkers, but it wasn’t a nervous breakdown."] In a few minutes, she would gather herself, get up and head for the kitchen to start preparing dinner.

Even my dad had his emotionally tough moments as he thought about the stressful times. He battled both Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis for years. He developed badly deformed and inflamed hands and joints were very painful to the touch. He got so bad and got to the point that his last ten to twelve years were torturous, needing much care, like what is now rendered in nursing homes today. He died in 1963 at the age of 75. Mom developed cancer. Had surgery to remove half or more of the stomach and did live about four more years before it reappeared. She died in July 1966 at the age of 75. Marjorie died in the year 2000. I will always miss them, one and all. [Note from daughter Janice: "Bob died March 12, 2020 at the age of 89, just three weeks shy of his 90th birthday. Aunt Dorothy lived the longest--until she was 92 years old."]

The Depression continues to affect people even today. Sometimes you hear stories about people who now hoard stuff because they didn't have anything before. We couldn't give things away; we used stuff until it fell apart. I guess we did a lot of things together as a family, too. We all did a vegetable garden. The girls did canning, and we put it in the cellar. It goes back to not wasting your time. Being industrious. I got upset with somebody who appeared to me to be lazy. Of course, going into the marines, you couldn't be lazy—unless you wanted to get kicked out. That's why I have to keep busy, I feel sluggish if I'm not doing something or not planning on doing something.

If a similar financial crisis like the Great Depression hit America today. I think Americans would fare poorly. I guess it would go on the basis that we didn't have credit in those days. It was pay as you go. Do all you can to not borrow money. They started to come out with payment plans at some of the stores, but that was looked down upon. It was like, why would you want to do that? While I was in the service and I was over in Korea, I sent allotment money home. I told my brother Don, “If I get out of here, see if you can find me a car.” I used to go on dates with my dad's greasy truck. Don bought the car for me. I never even saw it. I just wanted a Chevy convertible. That's what I had when I got married and went on my honeymoon.

World War II

Like everybody else, I heard the news about the outbreak of World War II on the radio. When the war broke out the government started the draft system. I was too young to be in the service, but my brother Art served with the 82nd Airborne Paratroopers Division (508). He was wounded twice and received two Purple Heart medals. He was shot in the jaw and took shrapnel in the leg during a combat jump in the Netherlands/Holland area. I don't recall how my folks received the news about his injury. I was in middle school at the time. He first took a hit through his lower jaw while descending from the plane. It must have been a small caliber round. It lodged in the jaw bone. They sent him to a hospital in England, and a few months later he rejoined his unit in time to make a second jump at the Battle of the Bulge area. This time he caught shrapnel wounds in his right thigh and hip area and he nearly died from loss of blood. He was put on a med-flight to England for surgery and rehab. He eventually was put on disability at a V.A. Hospital in the United States. Even though the leg injury was worse than the jaw injury, he recovered quite well from his wounds and then put on partial disability all his life.

My brother Dale was in the army also. He joined in 1943 and ended up in an artillery unity before he went to Europe following the Normandy Invasion. Most of his duty was near Belgium. He wasn't in any front line fighting that I know of. Those big Howitzers could fire up to twenty miles. He was in Europe at war’s end. I remember he shipped a large wooden crate home that contained an “over/under” three-barrel shotgun—a rifle used for hunting wild game. He also sent some German officers' swords and bayonets, a Lugar pistol, and other small items (contraband that he probably bought/traded for or won in a card game). I kept the crate under my bed until he got home. Most of the items slowly disappeared as he needed cash. Somewhere I still have couple of bayonets that he gave to me. my brother Don was deferred because an armistice had been declared by then. He was working for my dad and for the A&P. Ken was flat-footed, so they wouldn't take him in the army.

Brother Don and Ken married, as did Marj and Dorothy, and the crowded conditions at home slackened some. Kenneth worked as Assistant Manager at the local Piggly Wiggly. Ken and his wife Eleanor eventually moved to Glen Elynn, Illinois, and he went to work with the National Tea Company. He was in the retail and wholesale food business until he retired. Don became a butcher at the A&P and then worked with Dad in the family business. Marj started a hair salon before she and Carl Bergstrom moved to Alton, Illinois. Carl worked years for Illinois Bell. Art went to work for National Tea Company in 1945. He married Marjorie Lass from LaGrange in 1946. They had no children. He died of a sudden massive heart attack in 1978 in New Orleans while working for a franchise food chain. He was just 55 years old. Dorothy married George Bergstom (Carl’s brother) who was in the Marines—so they moved around a lot. George and Dorothy settled in Phoenix, Arizona. When George retired he went into real estate sales in Arizona. I should note for the record that George and Dorothy’s daughter Susan was Miss Arizona of 1962 and then fourth runner up in the Miss America beauty contest in 1963.

Joining Up

While Dale and Art were in the army, I was down at the bike shop almost every day in the summer time. My job was cleaning up and helping put bikes together, I was also the sweeper and the cleaner-upper who wiped the grease off of stuff. That's where I got my ability to clean.

Six months after my high school graduation, I enlisted in the Marines. I wanted to join the military and since they were drafting already, I decided to join the Marines. I wanted to choose that branch of the military so that I could go into something I could be proud of. I didn't know much about the marines before I enlisted, but Bill Belter's brother was in the marines. I talked to Bill's brother and liked what he said. He said marines had to be in shape and that they did more amphibious landings and not walking through the muddy fields. (I ended up walking through rice paddies in Korea!)

My buddy Bill Belter and I joined the United States Marine Corps together on June 16, 1948 at Navy Pier in Chicago. No promises were made to us by the recruiters. We had to take written, multiple-choice-answer tests to see what we might be qualified for. I wanted to get in the motor pool, but that didn't work out. Five months later I took my boot camp training at Parris Island, South Carolina. My mother and father were not aware that I was signing up. When I told them, Mom and Dad asked, “Why are you doing this?” They didn't want to take the last boy out of the family, but what could they say about it? I don't know if my dad said anything. .By that time my brothers Art and Dale were home from the war, but still assigned to the army.

My overall itinerary during my enlistment in the Marine Corps was as follows:

- November 1948 to March 1949—Boot Camp at Parris Island, South Carolina

- March 1949 to May 1949—Camp Lejeune, North Carolina 2nd Marine Division

- May 1949 to September 1949—Camp Pendleton CA, Oceanside CA/Signal Corp School, Morse Code, Message Center Code School

- September 1949 to January 1950—Back to Lejeune, North Carolina-1st BN. 6th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division.

- January 1950 to May 1950—Mediterranean Cruise on Light-Cruiser, USS Roanoke

- June 1950 to August 1950—Camp Pendleton, CA 1st Marine Division. Advanced infantry Training

- August 1950 to September 1950—Kobe, Japan Preparation for Inchon Korea landing.

- September 1950 to August 1951—Korea Operations, Inchon, Seoul, Chosin Reservoir

- August 1951 to September 1952—Camp Allen, Norfolk Virginia, Naval Retraining Base

Leaving for Boot Camp

No one saw me off to the train station. They just said goodbye from home. Everybody gave me advice. Some advice was useful and some of it wasn't. My mom didn't give me a hug. She wasn't much of a hugger. She was like a drill instructor. I wasn't going steady with anybody when I left for Parris Island, so Mom was the biggest letter writer to me while I was in boot camp. Mom took a lot. Because she had three boys who were active members of the military, she put three little US flags in two windows of our home.

We took a train from Chicago to Port Royal, South Carolina, with stops along the way. The stops included Cincinnati, Ohio, and Atlanta and Augusta, Georgia. I was in charge of nine others, including Bill Belter. The orders stated, “You are directed to conduct yourself with proper decorum while en route. Any misconduct by you or the men in your charge is punishable by disciplinary action.” I had to make sure they got meals, we got to Atlanta and picked up a bus in Augusta, Georgia, and that we all arrived at Parris Island.

I smoked on my way to boot camp. We had to buy our own cigarettes. I smoked Lucky Strikes and Camel cigarettes before I went into the military, even though my mom didn't like smoking or drinking. (My dad smoked, but not much.) I can't remember when I quit smoking, but it was a common thing at that time. I guess I was apprehensive on the trip to Parris Island, wanting to make sure that we all got there, and not really knowing what to expect. I didn't know what I was doing, so I wasn't nervous. Having a couple of older brothers who were in the service, I at least got clues what I was going to face.

The nine in my charge were:

1. Erdmann, Stanley John

2. Peterson, Stewart Hand

3. Vaughn, Richard Hamilton

4. Schulte, James Robert

5. Semiginowski, Daniel John

6. Schmidt, Allan Charles

7. Belter, William Rienhold Jr.

8. Albert, David Henry

9. Holschbach, Marvin Valentine

Other than visiting my Grandpa Pete in Winona a few weeks in the summer, this was my first extended time away from home. I had never been out of the State of Illinois except maybe we went out to Lake Geneva (Wisconsin) once. We never took vacations other than short ones to Streator, Pontiac, and Winona.

Parris Island

After entering the base for boot camp, they took roll call for all of us and we learned to take orders. We were given a utility uniform. All they had to do was look at us and they knew our size. I got my hair buzzed. That didn't bother me, but some of the guys from Chicago and Milwaukee—the guys with the zoot suits who had duck tails and curly hair that grew down their neck, broke out crying when they got shaved!

Our platoon number was 255. According to our official platoon photograph, our drill instructors were Sgt. P.H. Myers, Sgt. W.M. Nierman, and Sgt. J.H. Gacik. We had ten weeks of training where we learned how to march, how to clean weapons, how to take orders, and how to shine personal gear. We were given tests to learn what our strengths and weaknesses were. We learned how to shoot a rifle, and at the rifle range we had to qualify with an M1 rifle to become a rifleman. I passed. Toward the end of boot camp I practiced with a .45 pistol.

Our living quarters were barracks with a foot locker and lock and key. We had to make our own bed and put our clothes up. We wore dungarees and we had to press our own clothes. There were maybe twenty or thirty recruits. There were black recruits, but not too many. I didn't notice any prejudice toward them. I only knew Bill Belter from high school at the time, but became friends later with Bill Barks in communication-radio school. (Bill Belter died July 11, 2010 in Springfield, Illinois. William Richard “Bill” Barks died August 10, 2017 in Ohio.)

We had to get up at 5 a.m. by the bugle blowing. We took a shower and then had breakfast in the mess hall. We were fed well. We had a little slack time during meals, but an NCO was still in charge, so meals were somewhat regimented. After we ate we fell out and went back to the barracks to take care of personal gear. We shined our buckle and shoes. On different days we did different things. Sometimes it was classroom training. Other days it was marching, etc. I think we were awakened in the middle of the night maybe once. They wanted to see how we would react after only two hours of sleep.

Every day we were tested. Marching, hiking, jogging, running. They timed us. If we got a cramp we went to sick bay and they took care of us. We had to take classes on the rifle range and we had to meet minimal requirements coming out of boot camp. There were swimming tests. Some guys didn't know how to swim so they had to spend more time with lessons. One of the things we had to pass was to hold our breath and swim fifty yards. I learned to swim back home in Illinois in the Salt Creek. We got acquainted with different gasses and learned how to work the mask. We had to sing the Marine Hymn without a gas mask on, which meant we were crying due to tear gas in the little cabin that was the gas chamber. We didn't worry about cold weather training as it was in South Carolina coastal. Parris Island was semi-tropical, but it wasn't exactly a tropical paradise. There were mosquitoes and there were alligators. The alligators stuck to the water and we didn't see them much. There were a few armadillos. None of these caused grief to the platoon, but we always kept our eyes out for water moccasins.

Some of the D.I.'s were very strict. Some were not. They were picky about marching in formation, how our uniforms looked, if our shoes were in good shape, how we displayed our weapons and if they were clean. Physical discipline was given out, but it was nothing we didn't expect. If the gear was not clean or hung up properly and someone was a repeat offender, he got roughed up and shaken, and possibly special duty like cleaning garbage cans, etc. I personally didn't get into trouble, but I saw others who got extra yelled at or were assigned extra duty. It was the D.I.'s job to get the guys working together for the same goals. I always appreciated my D.I.s. They were not jerks. They didn't have a superiority complex. Our platoon didn't really have any troublemakers. Nobody went AWOL. Bill Belter was in my platoon and he got in trouble for smiling a lot. They told him to wipe the smile off his face. Some of the big city boys had trouble with boot camp, but I don't know why.

Church was offered. I went to church at the times they allotted because I wanted to worship God. About half of my platoon went and half didn't. Even on Sunday they planned things around church. “Fun” in boot camp consisted of writing letters home. We went to bars on the base and I drank Coke.

I was never sorry that I had joined the Marine Corps. I knew what to expect. Boot camp was hard physically, but it wasn’t as difficult as I had feared. The fundamentals of becoming a disciplined Marine were taught well, and I made the necessary adjustments in my life to obey and not let the nitpicking, harsh, intimidating threats get under my skin. As they say—keep your nose clean and make not waves and you’ll survive almost anything. We just followed instructions and listened to them scream at us: “YOU IDIOT!”

At graduation we had to march for the ceremony. Someone from my family came, but I can't remember who. I don't think it was my parents. I was glad that boot camp was over. I persevered. I was a proud U. S. Marine. I felt more confident. I knew that I was expected to follow orders and stay out of trouble. It gave me confidence to be a U. S. Marine.

More Training

I went home on a ten-day leave. I don't remember what I did, but I probably visited family and buddies and close mates. I wore my utility uniform. I'm sure people complimented me, but I don't remember. When leave was over, I went to Camp LeJeune, North Carolina, by bus and train. Nothing unusual happened on the trip.

Once at the training camp, I started more classroom stuff. I also had to get acquainted with other weapons such as machine guns, revolvers, M1's, grenades, bazookas, and mortar rounds, We had to learn how to detect other gasses. Rifle and target shooting consisted of firing from the knee, sitting, standing, and lying down. We were tested on our skills. The training I received at Camp LeJeune was more comprehensive than boot camp training. We were taught how to look out for ourselves and others.

The biggest challenge of infantry training for me personally was getting used to the gasses (laughing gas and tear gas), wearing the masks, and removing the masks. We had to go in the classroom without a mask and then they put gas in the room. We had to put our mask on before we passed out or got sick. Some gasses had their own odor. Sometimes we couldn't detect a gas because they had no odor. Sometimes we couldn't detect it until it went off. This training lasted about two weeks and it was on the base. We did not receive any cold weather training.

Communications School

Following some mundane duty and taking tests at LeJeune for determining a military operational specialty (M.O.S.) for a specialized school, I was reassigned to communications school at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California. I didn't receive that assignment at my request. They ordered me because that's where they needed me. I was okay with it and accepted it. I wanted to drive trucks, but the Marine Corps thought I would be better serving as a radio operator.

I attended communications school from March of 1949 to August 1949. The 19-week course was given in a classroom setting. I learned how to receive and send messages, naval procedures, operating procedures, message center, radio equipment, typing, and teletype. I learned to type on a typewriter, although I had had typing in high school. I learned how to operate a teletype machine, how to operate radio-audio equipment (a machine used to send and receive verbal messages), how to code and decode messages, and Morse code techniques. By the end of the course I was qualified as a radio operator-low speed (MOS 776), message center man (MOS 667), and teletype operator (MOS 237).

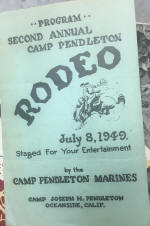

I don't recall liberty while at communication school, but the Oceanside Camp/School was a nice spot. I spent lots of afternoon on the beach and even tried surf-boarding. I also actually met John Wayne on a movie set at the beach. He, Forest Tucker, and Arleen Dahl were filming a movie (Sands of Iwo Jima) along the shoreline. I was busy taking pictures of all the other guys with John Wayne (using their cameras) and then forgot to get one of myself with him. There were many different events that were enjoyable and fun at Camp Pendleton. For instance, I was a spectator at the 2nd Annual Camp Pendleton Rodeo on July 8, 1949. Major General G.B. Erskine was the commanding officer at that time. I still have a copy of the rodeo program that lists all of the participants. Their names appear in the Appendix of this memoir.

I completed the communications course on August 5, 1949. After graduation I was sent back to Camp LeJeune and became a Radio Operator for an Infantry Company in the 6th Marine Regiment. A few months later I was ordered to go on a Mediterranean cruise. I loaded gear at Motörhead City, North Carolina, on January 3, 1950, left Camp LeJeune by bus the next day, and then boarded a train at Wilmington for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania the same day. I had liberty at Philly at night and visited with friends of Colonel Williams.

Mediterranean Tour

I boarded the USS Roanoke on January 5 at noon and she sailed at 1030 hours on January 6th. The Roanoke held up to 1400 officers and men. I knew Bill Barks and a few others. I think there were only Navy/Marine personnel on it, but I don't really remember. I don't recall if there was cargo on it that needed to be dropped off at any bases overseas. The only cargo was what went with the guys.

The ship headed out the Delaware River and into the Atlantic Ocean. I held the rank of Corporal and was assigned to B Company, 1st Battalion, Sixth Marines, Second Division while on the ship. Known as a “Mediterranean Tour”, its purpose was basically to uphold and enforce, if necessary, our foreign policies. It was a four-months duty from January 6 to May 23, 1950. We traveled to Gibraltar, Algeria, Cyprus, Arabia, Greece, Crete, France, Tunisia, Augusta, Messina, Spax, Cirus, Port Said, Jidda, Athens, Suda Bay, Genova, Thessaloniki, Naples, Marseilles, and Algiers—not necessarily in that order.

I had never been on a big ship before, so for a land-lover it was unforgettable. I got a little queasy during the ten weary days that we crossed the rough, wintry sea. Although the Roanoke was a fast light cruiser, it could run only as fast as the more slower ships in the convoy which were joining the Med Fleet. Among those ships were the carrier Midway, the cruiser Newport News, the destroyer tender Sierra, and the auxiliary ship Arneb. There was much tossing and turning, dipping and rising, which kept us 190 fleet Marines on board striving to keep from turning green. We hit rough weather on the trip. Ships always hit rough weather--the ocean is always moving. (At least we didn't travel through a hurricane.) It was kind of like being on a Ferris Wheel at a carnival—going up slow and coming down fast. My stomach and brain had to get used to that. The more we were on the ship, the better it got until everybody got their sea legs in one degree or another.

The USS Roanoke had orders to rendezvous at Gibraltar (the "Rock"), the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea, on January 16, 1950. We anchored and stayed in the Gibraltar Harbor for nearly six days. During that time we were not allowed liberty at the Rock. After leaving the Rock, the Navy held a week of sea exercises with other vessels of the 6th Fleet. We Marines were just spectators, but it was interesting.

Daily Life on the Roanoke

Our living quarters were very tight and had five decks. We had to crawl up the corners of the other guys' beds and roll into our bed. Our bed was a little two-inch mattress on springs. We could roll it up and carry it on our back if we wanted. There were little lockers for each guy. There wasn't much room at all. There was a bathroom with a shower. The fact that our quarters were tight didn't really cause a problem because of someone who was seasick. If someone was going to get sick they got up and went to the bathroom.

For entertainment we watched movies, played cards, and read books. I enjoyed the cruise. It gave me time to relax a little, write letters, watch the movies and do some work (exercises). We took turns at guard duty on deck. We also had further training. We had to get off and on the ship by rope ladder and we had weapons training. We did target practice on the ship. They put pennants up in the air like balloons and we tried to aim at them. We used a rifle or artillery piece.

At some ports we were allowed to disembark. At others we couldn't. It depended on the harbor and the countries. When we arrived at the ports, we worked on our equipment, had liberty, and did sightseeing. I purchased postcards for myself and also wrote on them and mailed them home to Mom and Dad. The liberty varied. At some ports we stayed two or three days.

Old World Cities

After Gibraltar and the week of watching sea exercises, the Roanoke headed to August, Sicily. The City of Syracuse, which the Apostle Paul visited, was an hour away. After a few days, we sailed around Sicily and put in at the beautiful city of Messina. The Marines had their first shore liberty. From Messina, we could see the Italian mainland and observe Mount Etna and its snow-capped peak. We had to get adjusted to the lire/dollar exchange rate. (At the time it was 625 lire to a dollar.) [Note: The lire was replaced by the euro in 2002.]

The Marine contingency held landing operations on the Island of Malta the first of February. It was our first experience of going over the side of the ship with full gear on (including my 55-pound radio). We gingerly descended down a rope cargo ladder (8-10 abreast) into landing barges, and headed for the beach. I always felt more secure on the beach.

We headed south from Malta and put in at Sfax-Tunisia for a short stay. From there we sailed northeast to Cyprus (Famagusta.). On a tour, some got to visit the Othello Tower—the scene of Shakespeare’s Great Tragedy. Some of us got to visit the city of Salamis where Barnabas was buried.

Leaving Cyprus, we headed for Port Said, Egypt, and then to the city of Suez at the mouth of the canal. Waking up that morning was strange as we went through the canal, moving slowly past Egyptian gun emplacements on the starboard (right) side and British sandbagged bunkers on the port side. If the facing troops had started a firefight, we would have been right in the middle, but all remained quiet as we sailed into the Red Sea and down to Jidda, Saudi Arabia. The Roanoke was the first U.S. vessel through the Suez Canal since before the Second World War. Jidda was the city where Lawrence of Arabia once had his headquarters.

We left Arabia on March 3, and sailed back across the Mediterranean to Izmir (Smyrna) Turkey. There we got to tour the ruined city of Ephesus. I found myself taking a renewed interest in the old world history from Turkey to Greece and Athens. I would have liked to tour Athens had I not run short of cash. (There was no loan office on board.)

From Greece we moved to the Island of Crete for another practice amphibious landing operation. From there we set sail for the west coast of Italy to the Port of Genoa, where Columbus was born. I found Genoa fascinating and not damaged from the war like many other cities were. A real surprise was running into a high school classmate at a local pub who was on a merchant marine vessel also anchored at the Genoa port. We had a little reunion there before the Roanoke sailed back to Greece for a week at Piraeus and Salonika. The more cash-loaded shipmates toured Corinth. Again I was scraping bottom on resources after Genoa.

We sailed back to Italy--the host country of Naples/Rome/Pompeii and Capri. I was able to join a tour (at a cost) to the Vatican, St. Peters, and even was in a group having an audience with Pope Pius XII. We toured the city, the catacombs, and a little of the Appian Way over two days.

We went to Marseille, France and visited Basilique Notre-Dame de la Garde church atop the highest peak in the city offering a great view of the entire city and harbor and the fleet. I did not find the French people very cordial to Americans at that time.

On May 6, we headed to Algiers, North Africa, then sailed on to Lisbon, Portugal, making preparations to head for home. The Fleet flag was turned over to the incoming 6th Fleet, then we pulled anchor and sailed for home May 15, 1950, arriving in Norfolk, Virginia, on May 23. We had to board a train and take a bus back to Camp Lejeune, arriving May 25. We soon began to hear about deployment to the Far East.

War Breaks Out

We were in Camp Lejeune when we began to hear about deployment to the Far East after news of North Korea’s sudden attack into South Korea reached us. I didn't know anything about Korea other than the Japanese lost control of Korea after World War II. I didn't want to go to war. Of course not. Nobody wants to go to war. At my enlistment I didn't know there was going to be a war; however, I signed up knowing that war was a possibility.

After a ten-day leave, most of those just off the Mediterranean cruise were ordered to Camp Pendleton, California. I had no personal effects or car to store. We packed up and headed west to Camp Pendleton. For the next eight weeks we went through intense training in the very hot and dry conditions at Pendleton. We had many twelve-hour days of rapid maneuvers and marches in full-pack, supplies and weapons, into rough terrain, hoping we didn’t step or fall on a rattlesnake--which were everywhere. After getting our shots, we found ourselves in San Diego harbor being loaded on the troop ship USS Buckner. It was around August 1st. We were well out in the Pacific when we found out our next stop—Kobe, Japan.

Bill Barks traveled on the same ship. The difference between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans is that the Pacific is calmer and a smoother ride. We hit one large storm and one smaller storm en route to Kobe. I had watch duty (the same as guard duty) on the ship. It could be six to eight hours duty looking to see if there were any enemy ships in the area or other boats out there. We also had lifeboat training and how to go up and down the net. We used a cargo net to get from the top deck to the lower deck to get into the landing crafts. There was really no trick to it—we had to hold on and use it like a ladder. Every day we had something to do about military protocol. I don't recall having any briefings about what was happening in Korea during the trip.

After approximately seventeen days the USS Simon Buckner arrived at Kobe, Japan, on August 15. I don't recall how long we were there, but we did have some liberty. We could go shopping and meet up with other friends. Three or four guys and I went to a diner and we wanted a milk shake. We couldn't speak Japanese and they didn't speak English, but we were able to persuade the owners of the diner to let us go behind the counter and make them.

While in Kobe we had more classroom training, plus live firing at an old Japanese Army range. We had to brush up on our radio/communications systems and procedures and check out our equipment. In September we went onboard LST troop carriers, and sailed around the Sea of Japan while other ships congregated into a sizeable fleet. After three or four days of going up and down the east coast of North Korea, the fleet made a U-turn and went around the tip of South Korea up into the Yellow Sea toward Inchon.

Inchon Landing

When we left Japan for Korea we were transferred to another ship. There were ships that went ahead of us to clear the beaches of any mines to make it safe when we landed. I'm not sure, but it may have taken about a week for them to do that. It took maybe two or three days to get from Kobe to Korea. We sailed around the Sea of Japan while other ships congregated into a sizeable fleet. After three or four days of going up and down the east coast of North Korea, the fleet made a U-turn and went around the tip of South Korea up into the Yellow Sea toward Inchon. From Kobe to the port of Inchon we were briefed on what was about to take place. I can't remember who did the briefing. This was most likely done the day before we landed. The mood on the ship was a little of “Let's go get them”, and hoping everything went well.

We loaded our gear into the landing crafts and they lowered the landing crafts down to the water. These crafts carried twenty or thirty troops. Then navy personnel drove the landing craft toward the beach. The weather conditions were good enough to make the landing, and the tide was right. (If the tides were too low, the ships couldn't get in.) The 1st Marine Division was ordered to land on three designated beaches spread out along the shoreline at Inchon: Blue Beach, Red Beach, and Green Beach. One company was to be dropped off at one location and then a hundred yards further there was another drop-off.

There were cruisers and larger landing craft in the vicinity of Inchon, but I didn't count how many. I remember fighter planes and some planes dropping bombs and the sound of boats and artillery fire. Britain had a few ships, but other than that I don't recall other ships that participated in the invasion. The navy had cleared the harbor of mines before we landed.

Early on the morning of September 15, after the big guns stopped firing, we loaded into LVT’s (smaller landing crafts) and headed toward the shore (designated Blue Beach), southeast of the city’s urban area. We landed on Blue Beach in the first wave. We immediately disembarked and moved to higher ground where there were designated areas for us to congregate. The first groups in had to get out of the landing crafts, walk up the shoreline, see where we were going to gather up, and see that everyone was accounted for. By the time we all got off the landing craft, it was four or five o'clock in the afternoon.

Landings never worked out just right. Our officers were always making adjustments on the way. They couldn't just put all of the marines in one little boat and say, “You go to Inchon” or whatever. They were organized into groups. During the landing they could be halfway down the shoreline. Then they had to get everyone back in their right groupings. They didn't give us any real instructions on what to do or not do about wading water up to our waist to get up on shore. There was lots of sand; it was rocky; and there was not good footing. We had to be careful what we stood on. We had to kind of climb over rocks and boulders that were normally in the water. There were big rocks to maneuver around and we tried to not get knocked on our rear-end. The moss near the shoreline was treacherous. It was slippery, so while we walked along rocks we tried not to fall and go under the water because that would get everything we were carrying wet. We didn't want that to happen. I felt safer on the water than I felt on the land going from the landing crafts to the shore.

I remember that Inchon was a good-sized, spread-out city. We secured Blue Beach and then came across a little resistance from the enemy. We were even greeted by the North Koreans. They had set up speaker systems. They blew horns and then we heard, “Welcome to Korea, Americans. Wouldn't you want to be home with your wives and children? Give up now and then you'll get home sooner.” That was their psychology.

Our platoon regrouped around the edge of Inchon city. The captain had his map and had the area where we were going to be. He had to make sure that we were all accounted for. (Some guys might have gotten washed out to shore and took longer to get back in.) We had to get to our assigned groupings and squads and get into the positions they wanted us to be in for that first night. Communications had to be in a certain order. We had to help unload supplies from Green Beach and help build a pontoon dock. We didn't have any problems. At least we didn't have to fight the elements. Rosters told us the ones who would patrol and watch for any Korean groups still in the area that didn't move out—hidden troops or hidden equipment.

With only moderate resistance we made good progress to cut off the east side of Inchon. We then had to find places to bed down that night and have machine guns ready. (I had my .45 ready.) There were two or three captains, staff sergeants, etc. They all had their assigned duties and we had to wait for the master sergeants or staff sergeants or whoever was in charge of our particular group. We had to dig our own “hotel” that night. The officers told us, “Okay. Start digging your foxhole. You twelve men dig your foxholes right here.” We did the best we could until daylight because there wasn't much we could do at nighttime.

Captain Corley's Radio Man

I was assigned as a low-speed radio operator in Howe Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division. I had a radio pack and my .45. My equipment was an SCR300 radio, and my job was to operate it. It was like having a telephone. With it we received orders and ordered supplies, and received messages about where the enemy might be, etcetera. As a radio guy, I was supposed to be up with the captain usually, and he was up in the front of his battalion or company; but I didn't really meet Captain Clarence Corley until the next day after we landed at Inchon.

I'll never forget Captain Corley. I liked him. He was more human. Not stuck up. He was kind of the fatherly influence of the guys. He didn't try to show off. He had a kind heart. Corley was a teacher. In fact, he had quite a career after Korea teaching about combat—things that worked well and things that didn't work well. I'm glad I had him because he was a little more down to earth. He was not one of those guys who said, “I know it all. Leave it all to me.” A radio operator gets to know his officer because he sleeps near him, eats with him, reads with him, etc. Captain Corley and I were just like brothers. I had to be with him night and day. I guess he kind of took a little extra precaution with me sometimes. He knew I was on a lot of patrols in a strange area. He had been in the South Pacific during the Second World War and had experienced some of the island skirmishes that they had. He was a young father who had two daughters who were probably grade school age.

On to Kimpo/Seoul

After securing the beach and spending the night, we packed up our gear and started heading toward Kimpo and Seoul. (Seoul was about fifteen miles away.) We had South Korean soldiers with us, so we had to have interpreters due to language problems. We left early in the morning at about 7:30 or 8:00 a.m. We didn't see any civilians out while en route to Kimpo.

There was an airstrip at Kimpo where we were to set up defenses and make sure the enemy didn't get it. [KWE note: Kimpo airstrip was originally built on a bed of rocks 1935-1942.] It was daytime and there was some engaging of the enemy, but they were pulling out because they were outnumbered. There were those in the company who were killed or wounded, but I wasn't taking a head count.

We probably had a few World War II Vets with us, but most of us were green troops—we didn't know any better. I had heard about combat from my brothers. They didn't fudge their stories. War was pretty much like they said it was. We had to always prepare ourselves that it was never going to be what we expected. If we expected too much, we would be in trouble.